Share this

Media Literacy in the Digital Age

by Ryann Garland on August 7, 2025

What is an Internet conspiracy that you have actually believed to be true? What’s a recent ‘headline’ you saw where it was unclear if it was real or not?

One of my recent ‘gotchya’ Internet moments was a post I saw claiming that an episode of The Simpsons from years ago accurately predicted and depicted a recent cheating scandal caught at a Coldplay concert. For a few days, this one had me believing the writers of The Simpsons must have a time machine before I realized it was fake news.

A few years prior to this, I had one of those awe-inspiring, life-changing moments where I realized that one of my purposes in life is pursuing, recognizing, and understanding truth. In the digital age, knowing what’s true feels like trying to justify your 2:00 AM doom scroll on TikTok: frustrating, never-ending, and always leaving you a little sleep-deprived.

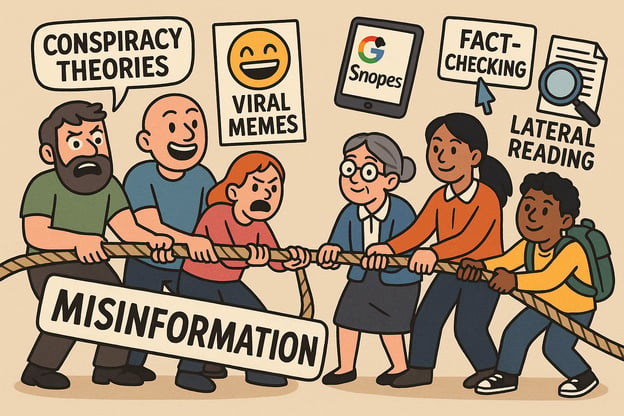

So how do we decide what’s true, what’s fake, and what has a little bit of both? The world of digital communication can be a scary place for a truth seeker—it’s full of apologists and anarchists. There are memes and cancellations and apology videos and essays and a whole slew of genres that are new and developing. There also, try as we might, are very few (if any) rules in the wild wild west of the World Wide Web. How can we bring up a generation of students who have seen no other world other than one full of memes and viral videos?

Entering the Reality-Based Community

American author and journalist Jonathan Rauch published a book in 2021 called The Constitution of Knowledge. In this, he explores what it means to be a defender of truth. What stuck with me the most from Rauch’s ideas is something called the reality-based community.

The reality-based community transcends language differences, political stances, and international borders. Members of the reality-based community are those who are firmly committed to sharing and defending truth, whether that is truth about a politician, a scientific discovery, or even the sobering truth about Pluto’s planet status (RIP). The reality-based community operates on a commitment to objectivity, factuality, and rationality. In short, the reality-based community is made up of people who are committed to figuring out what’s real, sharing what they learn, and helping others do the same.

Media literacy is also an essential skill for both students and teachers. In an evolving digital age, technology pushes us to think in new ways and communicate differently. The Carnegie Corporation of New York said, "If a central purpose of schooling is to prepare future generations to exercise their civic responsibilities, then educators must encourage students to investigate rather than doubt media sources. They go from being consumers to interrogators of news and information." Teachers play a key role in helping students grow into responsible digital citizens who can separate fact from fiction online.

These skills aren’t just reserved for internet activity either. Evaluating resources and identifying evidence for a claim are key skills for Common Core English Language Arts. Good readers and thinkers need to be able to navigate information in all kinds of formats: videos, tweets, and textbooks alike. Beyond ELA, media literacy can be incorporated into all other subjects even in ways as simple as sharing a recent news segment that relates to the day’s lesson and having students evaluate its reliability.

Here are three classroom-ready strategies that prepare students to be part of the reality-based community:

Working the Network

Common Sense Media reported that only 44% of students feel confident in distinguishing between fake and real news online. So how do we build this confidence in students?

Prior to my experience in a digital communication college course, fact-checking seemed like a concept beyond me. A duty to which I was not called. Someone else’s responsibility. However, I was committed to being a member of the reality-based community. I inherently have been given the responsibility to fact-check. Not just zooming out to examine an outlandish political tweet or determining if JK Rowling is actually a devil worshipper or not. Sure, that’s important for my civic and cultural life. I must zoom out on the most important truths presented to me.

Students need to zoom out too. It’s all about research, research, research. Part of strong literary skills is evaluating, analyzing, and summarizing sources; this includes discerning those sources that are reliable or not. Students can practice identifying what’s fake versus real through a Mission, or even by browsing some recent headlines.

Start by modeling fact-checking in class. Teach students strategies like lateral reading and using verified fact-checking sites like Snopes. For example, a teacher can present students with a series of news articles, social media posts, and other online content that is both true and not. It doesn’t need to be a high-level investigation, but this can be a simple and low-stakes activity to build student confidence.

Use Sources Wisely

With tools like ChatGPT and AI-driven search engines entering classrooms, source evaluation skills are more important than ever. Help students find the balance between the wise use of AI while also remaining cautious of its outputs. Part of fact-checking is knowing where one can find a reliable source. With the growth of AI and LLMs, I’ve noticed a serious disregard for the process of work. I myself have fallen victim to automation for the sake of speed. However, this doesn’t mean that AI needs to be disregarded completely. Tools like Canva, Quizlet, and Khan Academy have incorporated AI into their programs as a supplement, but not a replacement, to learning.

With these sources, whether AI or otherwise, reinforce that not all sources are created equal, whether a YouTube video or a Wikipedia page, teach students to ask: Who created this? Why did they make it? Can I verify this from another reliable source? Challenge students to even practice identifying phishing scams to strengthen their pathway towards responsible digital citizenship.

To apply this to the classroom, have students compare different accounts of the same event. This could be comparing a news reel and a blog post, a journal entry and a newspaper of a historical event, or anything in between. As students assess their sources, they should compare factors such as tone, evidence, and bias. To save on preparation time, check out some of our social studies Missions to give students even more practice with analyzing evidence.

Share your findings

Once confident in their facts, students can present their fact-checked findings and research to the class. This builds both communication skills and confidence in discussing what they’ve learned. Tools like Padlet are great for creating low-pressure and student-friendly spaces where students can share. Read about some of our other favorite platforms that make classroom collaboration and presentations a breeze here.

Creating a psychologically safe classroom is key. Students need to feel comfortable asking questions, sharing their confusion, and changing their minds when given new evidence.

Despite genre or medium, when we share our findings, share our experiences, and share our stories, we are inviting others to come participate in the reality-based community. We are inviting them to go back to step one and check the facts, use their resources, and for themselves come to the truth.

Think Better, Do Better

Start small: pick one headline, meme, or viral claim this week and fact-check it together with your students.

Media literacy isn’t just about preventing students from falling for a hoax. It’s about empowering them to think critically, ask better questions, and engage responsibly online. By teaching fact-checking, source evaluation, and thoughtful sharing, we help students build lifelong habits of truth-seeking. We prepare them to thrive in a world overflowing with information.

Share this

- February 2026 (4)

- January 2026 (4)

- December 2025 (3)

- November 2025 (1)

- October 2025 (4)

- September 2025 (2)

- August 2025 (6)

- July 2025 (9)

- June 2025 (8)

- May 2025 (6)

- April 2025 (4)

- March 2025 (4)

- February 2025 (1)

- May 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (3)

- November 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (1)

- September 2023 (4)